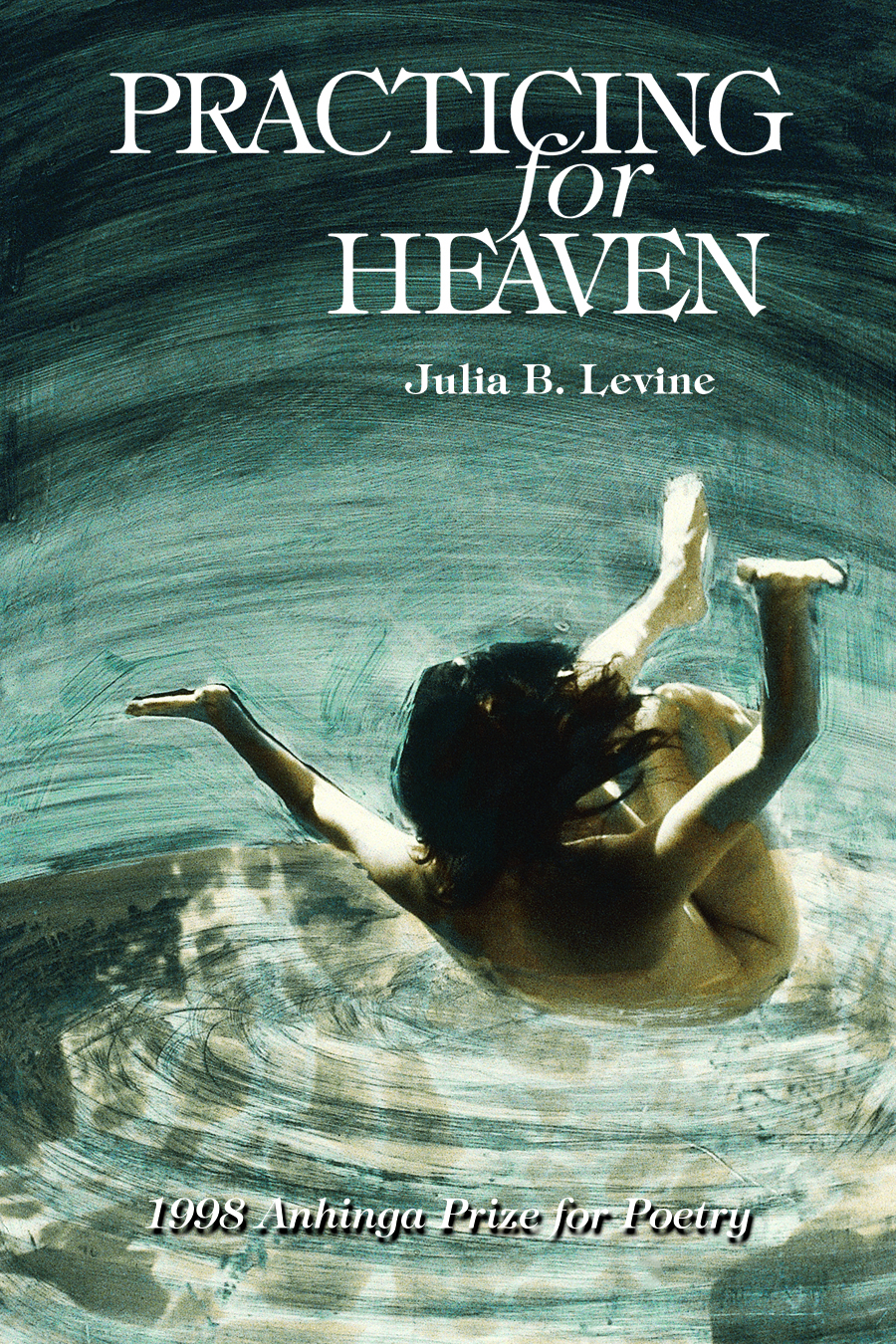

Practicing for Heaven by Julia B. Levine

Robert Dana-Anhinga Prize for Poetry (1998)

It's no exaggeration to say that reading Julia Levine's splendid first book, Practicing For Heaven, produces the illusion of living the life it depicts. Her image-rich, sensuous language combined with an unflinching faith in the power of specific detail create meaning viscerally rather than intellectually. Whether describing a walk beside the American River or a vigil at the bedside of a critically-ill spouse, Levine's poems reach us as directly as an infusion of blood. Hers is a delicate, elegiac, and truthful poetry with rare transcendental moments that the most cynical of readers can trust. -- Enid Shomer (Judge, 1998 Anhinga Prize for Poetry)

This is a luminous, breath-stopping book. Each poem is complete, each renders an intense encounter between the poet and what she loves: the "sensate world" in all its complexity of color, contour, and human emotion.... The eye makes us look while the words impel us toward feeling something of the poet's present -- a present charged with memories, hopes, and a sensitivity like that of the fontanelle: the soft spot on a baby's head invoked in one of the most striking poems in this brilliant first book. -- Margaret W. Ferguson

A lifetime of reading poetry tends to settle some of us more and more comfortably into those ‘ore-loaded rifts' of a few masters -- Dickinson, Horace, Keats, whomever. It takes a compelling new presence to return our attention to the plenitude of our own moment's efforts. Again and again I find this presence in the poetry of Julia Levine. More consistently than I could have imagined, her poems brim with a new and multi-faceted intelligence. I return to my own life hungry for more, wonderfully disturbed. -- Arthur Smith

My Gemini

Because she is waiting to be lifted

out of the silence of my unremembered life,

nothing can rinse her from what I carry

or how I travel these fields,

watching magpies scatter arrows into the sky,

and always knowing she slipped apart

from what was once seamless,

so that something of me, though torn,

would keep on arriving. Ahead of me

combines are spinning knives

deep into the ground,

leaving combs of threshed hay

to argue for a world that cuts everywhere.

This is how she wants me to walk,

steady and awake, into all that dies

before it can return, the last leaves

whispering further and further into silence,

these thistles bony with light,

and only the ravens black enough

to spill over with such a thin sun.

She wants me to touch it all,

knees bent in asters,

my fingers rattling petals,

remembering the months

she wrapped my mittened hand

back around the spoon, urging me to dig

down to the tiny locket

netted in the roots of our sugar maple.

She wants me to know even darkness

will speak if you listen, that each hidden word

asks to come to light,

that someday my body will call for her

to step back in.

Until then, she says,

we are practicing for heaven,

and this is how you get there,

the ladder built rung by rung

with the truth of whatever happens.

Nights on Lake Michigan

Downstairs, bitter voices wolved my door

and listening pulled the terror closer

until my room swelled with grim animals

stalking the forest around our cabin:

porcupines rasping bark off porch railings,

bats spitting darkness across the sleeping elms.

What child could have made another dream

from the bones of that cabin? At my window,

the lake soured into blackness. No moon yet.

If only I could have seen a path winding into morning

the way our rolling dock would stretch into the lake,

away from where my parents simmered in lounge chairs,

my mother tying up laces on three pairs of shoes,

my father devouring journals of disease,

his ear tuned to the peculiar music of the body's

pipes and strings. A path that would have led away

to where water held me as if my weight were sweet

and the underwater sand were rice paper

printed with tiny shells; away to where the wind rose up

as if someone called from the further shore,

whitecaps repeating my lost name. If only night

had been a smaller lake I could swim across,

where nightjars gently celloed in the rushes,

and sleep was how the silence borrowed me.

Fontanelle

1.

Stranded in that clockless month of her arrival,

I listen to our neighbor sawing down back doors,

and rock her, tiny fists of breath uncurling,

while the details of each afternoon are revealed:

that still hour before the mailman crosses the street

to unlock his grey tomb of letters, or after school,

children looking for a game to start, and finally

scarlet lights weeding the horizon,

when the men silence their tools and only darkness

bangs out across the empty lots. Now the homeless women

are shaking olives from roadside trees, black pellets

raining down on their plastic bonnets

as this room gathers us into the heart of the house.

Torn up from sleep,

without a memory of dreams, all that will remain

in the essential loneliness before dawn,

is blue milk running from my body

and the violence of her genderless desire

clamping down on my skin.

2.

And then as I stare mutely out the window

at the shut door of the world, there is a night of weather,

trails of light scarring blackness, pelting whip of rain

rattling the fenceline. As giant conifers

crack and fall in the cemetery, the dead around us

unable to hold onto that last tangled handful of roots,

I begin my journey through each child's room,

knowing I am not tending their fear, but my own,

that I will never again travel far enough away

to be injured, to feel wilderness jar against me.

I count the miles between lightning and thunder

as the distance narrows and then widens in retreat.

And when I return to summon you up from sleep,

how desperately I want that brief moment of overlap:

when what was seen can finally be felt, that brilliant flash

when the self finally marries what it was

with what it has become.

3.

As she begins to arrive within her body,

I dare touch the fontanelle,

a vein visibly pulsing under that taut canvas,

tiny plates of skull still undone. Outside,

empty songs of the builders' hammers

flush a handful of crows into the sky. All winter

between rains searing streets into rivers,

sandbags packed around the sewer's roaring throat,

workmen waited inside steamy cabs of their trucks

to forge that blue carbon into a neighborhood.

Now when I take her out among the dark scars

of newly rolled streets, sidewalks not yet lined

with chalk drawings or paired initials,

her eyes without vocabulary,

a hare bounds out ahead of us,

dark-tipped ears sliding between wall guides

of new houses that stand open, without secrets,

a forest of forms not yet fully seen:

the world just before it can be known.